Tentative Signs of Water Found on Moon

New data and images from NASA?s new moon orbiter ? the firstin more than a decade ? have revealed tentative signs of lunar water ice, thespace agency announced Thursday.

The powerful LunarReconnaissance Orbiter, or LRO, has successfully completed its testing andcalibration phase and entered its mapping orbit of the moon. The spacecraft'sinstruments have also made measurements of space radiation in the lunarenvironment and have found more widespread possible signatures of water on themoon.

"The LRO mission already has begun to give us new datathat will lead to a vastly improved atlas of the lunar south pole and advanceour capability for human exploration and scientific benefit," said RichardVondrak, LRO project scientist at NASA's Goddard Space Flight Center in Greenbelt, Md.

The first results from LRO's Lunar Exploration NeutronDetector, or LEND, indicate that permanently shadowed and nearby regions mayharbor water ice and hydrogen. LEND relies on a decrease in neutron radiationfrom the lunar surface to indicate the presence of water or hydrogen.

One big finding so far from LEND is that "the hydrogenis not confined to permanently shadowed craters," Vondrak said. Teammembers want more observations to confirm these findings and determine how significantthey are and how to interpret them.

"The power of LRO is that we're not just sending oneinstrument, like LEND, to look for hydrogen, we're characterizing fully"the lunar south pole, Vondrak said.

Jump on science

Get the Space.com Newsletter

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

The spacecraft, launched towardthe moon on June 18, is in good shape and set to begin its scientificmission in earnest, mission managers reported.

"The LRO instruments, spacecraft, and ground systemscontinue to operate essentially flawlessly," said Craig Tooley, LROproject manager at Goddard.

Mission scientists were able to get a jump on some of thescience objectives during the commissioning phase of the instrument and get someresults that mission officials emphasize are preliminary.

"But some of them are really intriguing too," saidMichael Wargo, chief lunar scientist at the Exploration Systems MissionDirectorate, NASA Headquarters in Washington, D.C.

The powerful $540 million orbiter,which is about the size of a Mini Cooper car, is on a one-year mission to seekout potential landing sites for future astronauts, as well as build new maps ofthe moon's surface, temperature extremes and radiation environment. It will alsohunt for water ice in the permanently shadowed craters of the moon's southpole. A source of water ice on the moon would be a boon to any future moonbases because it could be melted for water and hydrogen for fuel could beextracted from it.

First results

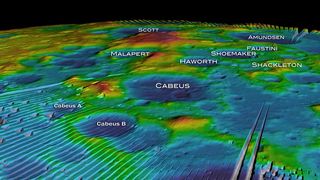

In addition to the initial LEND results, data from LRO'sLunar Orbiter Laser Altimeter, or LOLA, used to map elevation indicates thatexploring the moon?s south pole will be challenging because the terrain is veryrough. Some of the crater slopes that LOLA has measured are relatively steepand would be difficult to drive a truck or car over, let alone a moon rover,said David Smith, LOLA principal investigator at Goddard.

That roughness is probably a result of the lack ofatmosphere and absence of erosion from wind or water, Smith said. LOLA hasalready mapped a good portion of the lunar south pole, he added.

LRO's other instruments also are providing data to help mapthe moon's terrain and resources.

The probe?s Diviner instrument for mapping temperaturerevealed large, frigid expanses in the permanently shadowed craters are aboutminus 400 degrees Fahrenheit (minus 240 Celsius), "which is extremely coldand is much colder than the temperature needed to trap a volatile, such aswater," Vondrak said. In fact, these permanently shadowed regions"are perhaps the coldest part of the solar system," he added.

The team will monitor seasonal changes in the temperatureover the course of the mission. Currently, the lunar south pole is heading intosummer.

The moon up close

The Lunar Reconnaissance Orbiter Camera is providinghigh-resolution images of permanently shadowed regions while lightingconditions change as the moon's south pole enters lunar summer.

"By the end of this mission, we will fully characterizeand get he best possible information we can on the existence of hydrogen"on or below the lunar surface, Vondrak said.

But, "if you really want to find out what's below thesurface, you have to touch the surface," Vondrak said, which is where LRO'scompanion mission, the Lunar Crater Observation and Sensing Satellite, comes in

LCROSS will impact the moon's south pole on Oct. 9 togenerate debris that can be analyzed for signs of water. LCROSS'target crater, called Cabeus A, was announced by NASA last week.

Meanwhile, LRO's Cosmic Ray Telescope for the Effects ofRadiation instrument is exploring the lunar radiation environment and itspotential effects on humans during record high, "worst-case" cosmicray intensities accompanying the extreme solar minimum conditions of this solarcycle.

LRO has sent back several batches of images, taken by LROC,before this newest set, including a region known as Mare Nubium (or Sea of Clouds), the Apollo11 landing site, and the tracks from a difficult Apollo spacewalk.

- Video - Target Moon: NASA's New Lunar Scouts, Part 2

- Video - LRO's Road to the Moon

- Image Gallery - Full Moon Fever

Join our Space Forums to keep talking space on the latest missions, night sky and more! And if you have a news tip, correction or comment, let us know at: community@space.com.

Andrea Thompson is an associate editor at Scientific American, where she covers sustainability, energy and the environment. Prior to that, she was a senior writer covering climate science at Climate Central and a reporter and editor at Live Science, where she primarily covered Earth science and the environment. She holds a graduate degree in science health and environmental reporting from New York University, as well as a bachelor of science and and masters of science in atmospheric chemistry from the Georgia Institute of Technology.

Most Popular