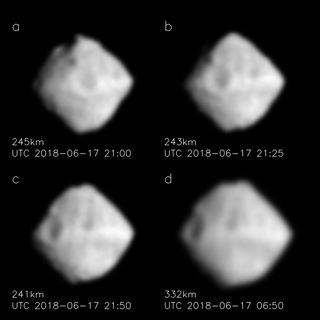

Japan's Hayabusa2 Asteroid Probe Snaps Best Pics Yet of Its Target Ryugu

As Japan's Hayabusa2 spacecraft approaches the asteroid Ryugu, the probe has grabbed its best photos yet of the rocky body — and they'll only get better.

The spacecraft, which launched in 2014, is set to arrive at the 3,000-foot-wide (900 meters) asteroid on or around June 27. After arriving, the probe will drop three rovers and a lander onto the space rock's surface to explore and grab samples.

The newest asteroid views reveal that Ryugu is a world of dramatic angles, covered with dents and craters, rotating in the opposite direction that Earth and the sun are as the object orbits. According to the newest data, the asteroid rotates fully around, perpendicular to its orbit, every 7.5 hours. [Photos: Japan's Hayabusa2 Asteroid Mission in Pictures]

"When I saw these images, I was surprised that Ryugu is very similar in shape to both the destination of the US OSIRIS-REx mission, asteroid Bennu, and also the target of the previously proposed MarcoPolo-R mission by Europe, asteroid 2008 EV5," Makoto Yoshikawa, the mission's manager for the Japanese space agency JAXA, said in a statement on June 19. Bennu and 2008 EV5 are smaller and rotate faster than Ryugu, but they have simple composition, Yoshikawa added. "So, we have both differences and similarities that have combined to produce very similar shapes ... why is that?

"So far, the asteroids we have explored have been different in shape [from each other], so Ryugu and Bennu could be the first time two similar-shaped asteroids have been examined," he added. "It will be interesting to clarify exactly what this similarity means scientifically."

After its arrival, when Hayabusa2 will be just 12.5 miles (20 kilometers) above Ryugu, the probe will drop a small lander and three rovers between September and next July.

The spacecraft will also hit the asteroid with an impactor, creating an artificial crater and then descending to collect material from below the surface that this crater reveals. Then, the probe will head back to Earth, arriving near the end of 2020 bearing samples for analysis.

Get the Space.com Newsletter

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

But all that work depends on correctly mapping the asteroid now, so scientists can choose the best places to land, the researchers said.

"If the axis of rotation for Ryugu is close to the vertical direction in this image, there is a big advantage, as it will be possible to know almost the entire appearance of Ryugu at an early stage after arrival," Yoshikawa said. "This makes the project planning easier.

"However, it is also possible that potential landing sites may be limited to the equator of Ryugu," he added. "I hope we can find a suitable place to set down the lander and rovers."

Email Sarah Lewin at slewin@space.com or follow her @SarahExplains. Follow us @Spacedotcom, Facebook and Google+. Original article on Space.com.

Join our Space Forums to keep talking space on the latest missions, night sky and more! And if you have a news tip, correction or comment, let us know at: community@space.com.

Sarah Lewin started writing for Space.com in June of 2015 as a Staff Writer and became Associate Editor in 2019 . Her work has been featured by Scientific American, IEEE Spectrum, Quanta Magazine, Wired, The Scientist, Science Friday and WGBH's Inside NOVA. Sarah has an MA from NYU's Science, Health and Environmental Reporting Program and an AB in mathematics from Brown University. When not writing, reading or thinking about space, Sarah enjoys musical theatre and mathematical papercraft. She is currently Assistant News Editor at Scientific American. You can follow her on Twitter @SarahExplains.