Mars Rover Curiosity Takes a Break to Survey Conquered Terrain (Photos, Video)

NASA's Mars rover Curiosity recently took a quick break from its mountain-climbing work to reflect on its epic Red Planet journey.

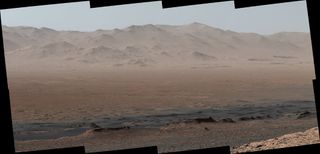

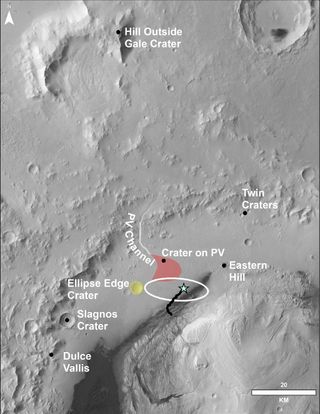

About three months ago, the car-size robot captured a series of photos from Vera Rubin Ridge, more than 1,000 feet (300 meters) above the floor of Mars' 96-mile-wide (154 kilometers) Gale Crater. Mission team members have stitched these images into a panorama that shows some of the key regions Curiosity has explored since touching down on the Red Planet in August 2012. [Photos: Spectacular Mars Vistas by NASA's Curiosity]

"Even though Curiosity has been steadily climbing for five years, this is the first time we could look back and see the whole mission laid out below us," Curiosity project scientist Ashwin Vasavada, of NASA's Jet Propulsion Laboratory in Pasadena, California, said in a statement Tuesday (Jan. 30).

"From our perch on Vera Rubin Ridge, the vast plains of the crater floor stretch out to the spectacular mountain range that forms the northern rim of Gale Crater," Vasavada added.

Curiosity's landing site is hidden behind a small hill, but "Yellowknife Bay" — the spot where the rover first found evidence that Gale hosted a potentially habitable lake-and-stream system long ago — is visible, mission team members said. So are other important locales, such as "Kimberley" and "Murray Buttes."

Much of Curiosity's work at such sites involved analyzing samples from the interiors of rocks, which the rover snagged using the rock-boring drill at the end of its robotic arm. That drill has been out of commission since December 2016, sidelined by a problem with the motor that pushes the drill bit forward relative to two "stabilizer points" on either side of it.

Curiosity team members have been troubleshooting this issue for more than a year now, and they've come up with a possible solution: using the robotic arm to push the extended bit against a rock, without the use of the stabilizer points.

Get the Space.com Newsletter

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

Tests of this new method using a Curiosity twin at JPL have been promising, and the mission team aims to try the technique out for real before the rover leaves Vera Rubin Ridge, NASA officials said.

Follow Mike Wall on Twitter @michaeldwall and Google+. Follow us @Spacedotcom, Facebook or Google+. Originally published on Space.com.

Join our Space Forums to keep talking space on the latest missions, night sky and more! And if you have a news tip, correction or comment, let us know at: community@space.com.

Michael Wall is a Senior Space Writer with Space.com and joined the team in 2010. He primarily covers exoplanets, spaceflight and military space, but has been known to dabble in the space art beat. His book about the search for alien life, "Out There," was published on Nov. 13, 2018. Before becoming a science writer, Michael worked as a herpetologist and wildlife biologist. He has a Ph.D. in evolutionary biology from the University of Sydney, Australia, a bachelor's degree from the University of Arizona, and a graduate certificate in science writing from the University of California, Santa Cruz. To find out what his latest project is, you can follow Michael on Twitter.