Extraterrestrial Gold Rush: What's Next for the Space Mining Industry?

HOUSTON -- If humans eventually want to become a space-faring species, we'll need to be able to collect basic resources, like water, straight from the space environment; it's too expensive and risky to send everything up from Earth, most experts agree.

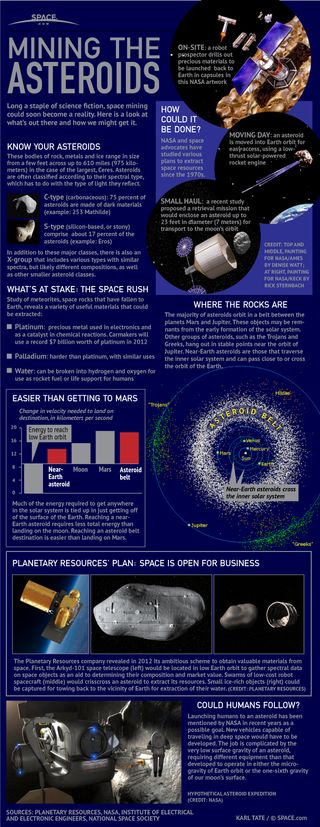

As such, multiple companies are now trying to initiate a space mining industry, which could provide those basic resources for space travelers, or for robotic space operations. In the future, asteroids or the moon could even provide humans with resources that are rare on Earth, such as precious metals.

But there are major hurdles that need to be overcome before space mining can get off the ground, so to speak. Representatives from various companies pursuing space mining activities recently spoke about the state of the industry here at the 2016 Space Commerce Conference and Exposition. [How Asteroid Mining Could Work (Infographic)]

The space mining supply chain

Many of the speakers on the panel made comparisons between space mining and terrestrial coal mining or offshore oil and gas drilling. Among other issues, that comparison leads to the idea of a mining supply chain, which refers to the activities that support the actual extraction of the desired materials. In terrestrial mining, that could mean everything from the team that surveys the land to find the best place to extract material, to the company that supplies food to the miners.

"The supply chain has a real place in terrestrial mining, and I'm suggesting that it also has a real place in off-planet mining," said Dale Boucher, CEO of Deltion Innovations Ltd., which has been working with NASA to build robotic mining technology for the moon.

Boucher said that for terrestrial mining, the supply chain can be broken into four major categories: exploration (to find a site that contains the stuff a company wants to mine for), development (essentially setting up an infrastructure to support the mining activity), operations (actual mining), and closure (on Earth, this typically entails returning the mining site to nature).

Many terrestrial mining companies rely on outside companies to provide various aspects of the supply chain, and the same will likely be true for space mining companies, Boucher said. Therefore, there is an opportunity for other groups to get involved in space mining without actually doing the mining themselves.

Get the Space.com Newsletter

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

"During the gold rush, if you're going to be in the supply chain, you don't want to be doing the actual mining," he said. "What you want to be doing is selling the 50 pounds of flour and 10 pounds of baking grease to the guys who are going up there and struggling and looking for gold," he said.

Another speaker on the panel, Chris Lewicki, president and CEO of Planetary Resources, made another comparison between space mining and the gold rush.

"I would love to be the first gold miner in Sutter's Mill [in California] and in the Yukon [in Canada], where gold mining [consisted of] walking up the street and picking up the shiny things," he said. "And what people don't realize is that space resources will, in a sense, start from a base that is very similar to that."

In the early days of space mining, companies may find that the materials they are pulling out of the moon or asteroids are relatively abundant and easy to collect, and that competition is low, Lewicki said. That means companies won't have to produce a large amount of product in order to make a profit.

"Low return, low production; basic technology is how this starts," he said.

Of course, traveling to those space resources is much more difficult than walking up the street to the creek to pan for gold, Lewicki noted. In addition, building a supply chain for space mining will be extremely difficult, some of the speakers pointed out.

Daniel Faber is CEO of Deep Space Industries, a company interested in exploration missions for space mining. Faber said the cost of launching those exploration spacecraft is so high that it might make those exploration missions impractical.

"Launch is the biggest thing slowing us down right now," he said. "We can do an exploration campaign for $3.5 million. But the launch is going to cost us 10 [million dollars]. And that's a boot in the teeth for an exploration company."

What will be mined, and who will buy it?

Many asteroids in the inner solar system are rich in metals, including those in the platinum group, according to Jim Keravala, chief operating officer of Shackleton Energy, another company with moon mining ambitions. Metals in that group have many applications on Earth, including in fuel cells and electronics. So people have discussed the possibility that these materials could be mined in space and be sent back to Earth, he said. That would depend on the cost of mining those materials and sending them back to Earth, and how that compares with the cost of mining those resources on Earth. Factored into that is the availability of those metals on Earth, Keravala said.

"The majority of rare earth minerals generated today, terrestrially, are from China, which is a real risk to our industries in the United States," Bob Lindberg, vice president for flight systems at Moon Express, said during the panel. Moon Express is the first private company to secure government approval to fly a spacecraft to the moon; their long-term business plan includes mining the moon for resources.

But all of the panelists seemed to agree that mining asteroids for minerals (and sending them back to Earth) doesn't make sense in the immediate future. Rather, they said, there's a more immediate resource that space mining companies should pursue: water.

Sending a full, 16-ounce water bottle into space currently costs about $2,500, Faber said; an Olympic-size swimming pool of water would cost about $1 billion. (That's why water is used sparingly on the International Space Station, and liquids are recycled.) Water is not only needed to keep astronauts alive; it is used in cooling systems on the space station, and could be used as fuel for spacecraft, according to some of the speakers.

Deep Space Industries is developing a water-based thruster to use on its asteroid exploration spacecraft; that thruster could also help kick-start a market for water as a fuel. Faber said many near-Earth asteroids are "about 20 percent water by weight" and that extracting water from those asteroids is a "relatively easy process."

Space launch provider United Launch Alliance (ULA) recently announced plans to have 1,000 people in space by 2045. Part of that plan involves a new rocket stage called Advanced Cryogenic Evolved Stage (ACES), which could help move people around in space. ULA representatives said it is possible that the rocket stage will use a fuel made from water.

Keravala said that previously, some members of the industry anticipated that water could be used to fuel communications satellites. However, that market seems to be closing as those satellites instead rely on electronic systems and solar energy. But one market he anticipates opening up will be robotic space stations that serve as science or manufacturing platforms. These stations could provide a place for companies to do microgravity experiments or manufacture things such as crystals or pharmaceuticals, he said. (Some crystals and molecules grow into unique arrangements in the absence of gravity; some are unique growth structures, while others may one day simply be cheaper to manufacture in space rather than in an Earth-based facility.)

But Lewicki noted that a market for water extracted from asteroids isn't currently up and running, so companies have to balance the lack of current customers with the potential for future customers.

"Whether you are a space agency or an entrepreneur, you're creating something that has to be worth something to someone, and right now, water on any near-Earth asteroid in the solar system is worth absolutely zero," he said. "It's worth absolutely nothing until we can develop it, figure out how we can use it, [figure out] what is the path from here to that future."

Farber closed by noting that, in order for space mining to thrive, there will need to be multiple players and the opportunity for collaboration.

"There's a whole bunch of things that we need to do to build resiliency into the supply chain, and that's best done with a lot of different actors working on different technologies, at different ends, and also cooperating," he said.

Follow Calla Cofield @callacofield. Follow us @Spacedotcom, Facebook and Google+. Original article on Space.com.

Join our Space Forums to keep talking space on the latest missions, night sky and more! And if you have a news tip, correction or comment, let us know at: community@space.com.

Calla Cofield joined Space.com's crew in October 2014. She enjoys writing about black holes, exploding stars, ripples in space-time, science in comic books, and all the mysteries of the cosmos. Prior to joining Space.com Calla worked as a freelance writer, with her work appearing in APS News, Symmetry magazine, Scientific American, Nature News, Physics World, and others. From 2010 to 2014 she was a producer for The Physics Central Podcast. Previously, Calla worked at the American Museum of Natural History in New York City (hands down the best office building ever) and SLAC National Accelerator Laboratory in California. Calla studied physics at the University of Massachusetts, Amherst and is originally from Sandy, Utah. In 2018, Calla left Space.com to join NASA's Jet Propulsion Laboratory media team where she oversees astronomy, physics, exoplanets and the Cold Atom Lab mission. She has been underground at three of the largest particle accelerators in the world and would really like to know what the heck dark matter is. Contact Calla via: E-Mail – Twitter