Neptune's Strange Magnetic Field Stretches Arms in New Model (Video)

Scientists knew Neptune's magnetic field was strange — just not this strange.

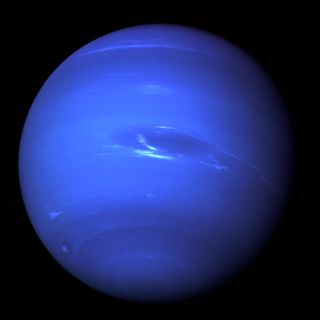

Neptune, the eighth planet from the sun, has vivid blue clouds and fierce windstorms, but also a badly behaved magnetic field. The field is 27 times more powerful than Earth's and sits at an angle on the planet, changing chaotically as it interacts with the solar wind.

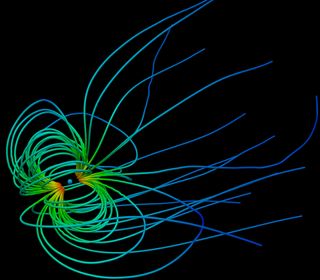

Researchers reconstructed the distant planet's magnetic field by combining data gathered by NASA's Voyager 2 probe in 1989 with a new model that was originally built to describe how plasma acts in the lab. The new results paint a picture of a field continuously in flux, tilted and bubbling out to one side, researchers said. [Photos of Neptune, The Mysterious Blue Planet]

"You can't take a picture of the magnetosphere, the 'bubble' that the planet's magnetic field carves in the solar wind, because it's invisible to the naked eye — everything is derived from the local measurements that the spacecraft made as it flew through," Jonathan Eastwood, a physicist and space scientist at Imperial College London, told Space.com.

In the new model, "we see that the magnetosphere is quite asymmetric, bulging out on one side," Eastwood added. "The old cartoons were quite symmetric."

Eastwood's group, working with plasma physicists, used a supercomputer to model the behavior of the superheated, supercharged state of matter in Neptune's magnetosphere. Specifically, they modeled how this matter interacts with ions streaming from the sun and the planet's rotation to shape a magnetic field. The magnetic interaction is particularly complex because Neptune rotates on a tilted axis compared to the sun, and the planet's magnetic field is tilted even more than this.

"Imagine taking the Earth, tipping it over diagonally, and then moving its magnetic north pole to central Europe, and you start to get a sense of what Neptune is like," Adam Masters, a planetary scientist also from Imperial College London, said in a statement. "The planet's unique magnetic field is still very poorly understood, and our new modeling represents a big leap forward."

Get the Space.com Newsletter

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

As they push on, the researchers hope to examine how the magnetosphere changes during different times of the Neptune year and how it interacts with Neptune's largest moon, Triton.

Besides deciphering some of Neptune's puzzling data, the newly adapted model could be useful in understanding what happens on Earth as this planet's magnetic field interacts with the sun — maybe even giving earlier warning of geomagnetic storms and their effects on the surface.

"We started doing this modeling for the purposes of space weather on Earth, so that's our overall, overarching goal," Eastwood told Space.com. "These simulations could be another tool that space-weather forecasters might be able to use, complementing existing computer simulations that are currently available."

The researchers are presenting their findings Wednesday (July 8) at the Royal Astronomical Society's National Astronomy Meeting 2015 in Wales.

Email Sarah Lewin at slewin@space.com or follow her @SarahExplains. Follow us @Spacedotcom, Facebook and Google+. Original article on Space.com.

Join our Space Forums to keep talking space on the latest missions, night sky and more! And if you have a news tip, correction or comment, let us know at: community@space.com.

Sarah Lewin started writing for Space.com in June of 2015 as a Staff Writer and became Associate Editor in 2019 . Her work has been featured by Scientific American, IEEE Spectrum, Quanta Magazine, Wired, The Scientist, Science Friday and WGBH's Inside NOVA. Sarah has an MA from NYU's Science, Health and Environmental Reporting Program and an AB in mathematics from Brown University. When not writing, reading or thinking about space, Sarah enjoys musical theatre and mathematical papercraft. She is currently Assistant News Editor at Scientific American. You can follow her on Twitter @SarahExplains.

Most Popular