How Zero Gravity Affects Astronauts' Hearts in Space

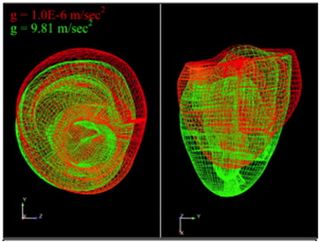

When astronauts spend long periods of time at zero gravity in space, their hearts become more spherical and lose muscle mass, a new study finds, which could lead to cardiac problems.

The physiological changes have implications for how manned missions to Mars and other extended trips in space could affect astronauts' health, according to research presented March 29 at a meeting of the American College of Cardiology in Washington, D.C.

"The heart doesn't work as hard in space, which can cause a loss of muscle mass," study leader Dr. James Thomas, Moore Chair of Cardiovascular Imaging and Lead Scientist for Ultrasound at NASA, said in a statement. "That can have serious consequences after the return to Earth, so we're looking into whether there are measures that can be taken to prevent or counteract that loss." [The Human Body in Space: 6 Weird Facts]

Given these effects, knowing what amount and kind of exercise could keep astronauts healthy will be important for ensuring astronauts remain healthy on long space missions. The same exercise regimens could help people on Earth who have severe physical limitations or heart failure to stay healthy, Thomas said.

In the study, Thomas and his team trained 12 astronauts to image their hearts using an ultrasound machine on the International Space Station. Images were taken before, during and after the astronauts' time in space.

The images revealed the heart becomes 9.4 percent more spherical in space. Mathematical models predicted the change almost exactly, Thomas said, adding that these models will give doctors a better understanding of heart conditions on Earth.

The spherical shape of the heart could mean the heart is functioning less efficiently. The condition appears to be temporary — the astronauts' hearts returned to a normal elongated shape after they return to Earth. Scientists don't know if the change has any long-term effects, however.

Get the Space.com Newsletter

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

The researchers are now adapting their models for conditions such as coronary artery disease (the most common type of heart disease and leading cause of death worldwide), hypertrophic cardiomyopathy (thickening of the heart muscle that limits its ability to pump blood) and diseases of the heart valves.

Follow Tanya Lewis on Twitter and Google+. Follow us @Spacedotcom, Facebook and Google+. Original article on Space.com.

Join our Space Forums to keep talking space on the latest missions, night sky and more! And if you have a news tip, correction or comment, let us know at: community@space.com.